Déjà vu on Grammar Schools: how pupil power overthrew delusion and division

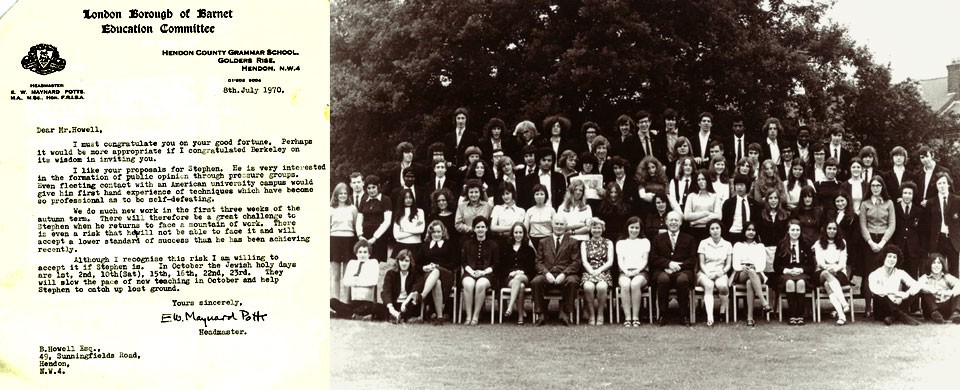

Hendon County, 1971, Lower Sixth: Peter Mandelson (front row, second from left), Steve Howell (third row, fourth from left) and Keren Abse (third row, third from right).

A note in my 1969 diary, when I was 15, suggests that my fellow pupils should “discuss the possibilities of comprehensive education in this school and then make a motion which will be put to the staff”.

Reading it now, I am not sure whether to be proud that I was politically precocious or embarrassed I was so naïve. In the cocoon of Hendon County Grammar School, it seems I thought political change could be ordained by my teachers when even five years of a Labour Government committed to abolishing the 11-plus had failed to shift the Dinosaurs of Barnet Borough Council.

But there were grounds to think Hendon County staff had special powers. They did, after all, march around in gowns and run the school like we were all destined for Oxbridge and great things beyond.

The architect of this quasi-public school atmosphere was E W Maynard Potts MA MSc, as he liked to sign himself. Potts had been running the school in an elitist way for three decades and his resistance to change matched the stubbornness of the council.

The local primary schools were feeder factories for Potts’ delusions of grandeur. I had attended the nearby St Mary’s Church of England School where at the end of the second year (Year 4 in new money), the children were divided between two classes deemed to have the potential to pass the 11-plus and a third for the ‘no hopers’ who were put in the temporary classroom in the playground.

By what cruel thinking 9-years-olds could be dumped on the rubbish heap like that is beyond me, but this was an era when there were still children’s books about ‘Little Black Sambo’ and our school uniforms were supplied by an outfitter who was renowned for squeezing the backside of every boy who ventured into his changing room.

The St Mary’s 11-plus treadmill duly discharged most of the chosen ones into Hendon County and other nearby grammar schools, and the social divide between peers from the same area became entrenched. I cannot recall having any friends from secondary modern schools, not – I like to think – because I was a snob but simply because that was the way it was. Yet Hendon County was by no means at the top of the social tree: above us were the private ‘direct grant’ schools such as Haberdashers and UCS and beyond them were public schools we viewed mainly through the lens of Jennings and Billy Bunter novels.

Like a manager of Cardiff City competing with Manchester United, Potts did his best to give the truly-elite a run for their money. He rooted out anyone deemed fit only for “selling matchsticks” (as he would put it to some of the girls) and compelled everyone to choose their A level subjects at 14 so they could by-pass them at O level and start the A level curriculum early. It worked if you measure success purely by university admissions, but two of my most successful friends were among the casualties of his limited vision.

What I did not know when I wrote that diary entry in 1969 was that Potts was fighting a losing battle and that my naïve desire for change would play a part in his downfall. Around that time, my Labour stalwart grandmother, Winnie, had persuaded me and a schoolfriend, Peter Mandelson, to form a branch of the Young Socialists in Hendon. Supported by another friend, Keren Abse, we managed to draw around a third of our school year into a YS campaign to turn Hendon County into a comprehensive school through a merger with the nearby St David’s School. That campaign was almost certainly destined for success without our modest contribution because of the wider winds of change, but what really finished Potts was his miscalculation of the mood in the school.

In a transparent attempt to buy us off, Potts made Peter and me prefects in the summer of 1970, ready for the start of the sixth form that autumn. For Peter, becoming a prefect was expected. But I was somewhat perplexed, especially as I had been caned by Potts for being disruptive in class only a year or two earlier.

I didn’t give it much thought, though, because I had more exciting things on my mind: my father, who was from the US, had been invited to be a visiting professor at Berkeley and I was about to spend most of the summer travelling from New York to California. The trip required the approval of Potts because I would miss the start of term, and he was typically ungracious in giving his blessing. In a letter to my father, he said: “(Stephen) is very interested in the formation of public opinion through pressure groups. Even fleeting contact with an American university campus would give him first-hand experience of techniques which have become so professional as to be self-defeating.”

But, in fact, no professionalism was needed to oust Potts. When I came back from the US, while my parents remained in Berkeley, I decided to suggest that Hendon County’s separate prefects’ common room should be open to everyone in the sixth form. The proposal, which Peter supported, was narrowly carried at a prefects meeting. However, the next day, Potts sent his deputy head to a reconvened meeting to tell us the common room wasn’t ours to share and would be turned into a stock room if we didn’t reverse the decision. That swayed enough people to over-turn the vote, and the dissident prefects – a dozen of us – were now so incensed we resigned and demanded the replacement of the prefects system itself by a school council.

Our stand was spontaneous, taken within hours of the second meeting without any plan or professionalism, but it struck such a chord with fellow pupils of all ages that those who remained as prefects were labelled scabs and booed as they walked around the school in their gowns. Potts was apoplectic and, as Peter describes in his autobiography, The Third Man, denounced us in a school assembly as “industrial militants trying to tear apart the fabric of our school community”.

That proved to be virtually his last gasp as an autocrat resisting change. He had – to return to football language – lost the players. At the end of that term, he took early retirement and was replaced by an acting head from outside the school who abolished the prefects system and delivered the merger with St David’s ready for the start of our upper sixth year.

It was too late by then for comprehensive education to have much impact on me personally, but what I do remember is how well the two football and athletics teams came together and the brief friendship I forged with Frank Attoh from St David’s. Frank was a good footballer and a brilliant athlete, and would prove to be an even better coach. He went on to represent Great Britain in the triple jump and, more recently, to nurture some of our best athletes, including double world indoor champion Ashia Hanson.

It was undoubtedly my loss that grammar school elitism had kept us apart – but, more importantly, I wonder how many thousands of 9-year-old spirits were crushed in 11-plus ‘no-hoper’ classes like the one at St Mary’s.

Steve Howell

Steve is author of Over The Line, a novel set in the steroid underworld of South Wales, which is available on Kindle (£1.99), Kindle Unlimited (free to subscribers) and in paperback (7.99) via Amazon, Waterstones and other booksellers. The paperback can also be purchased (post free in the UK) using PayPal via this website – ORDER