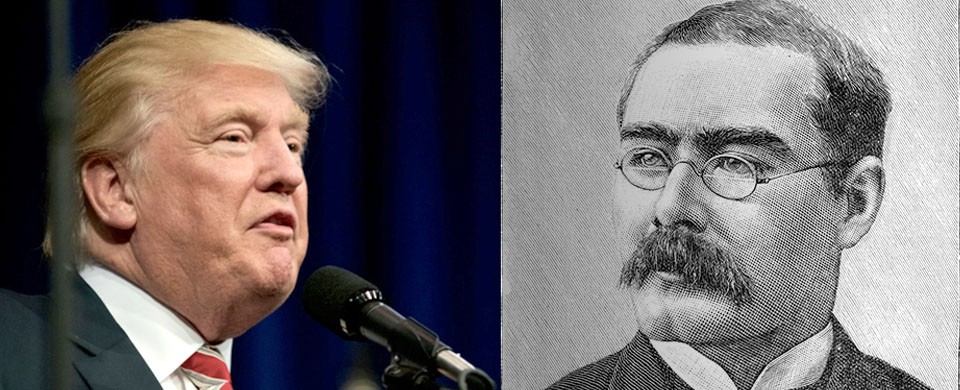

Theresa May echoes Kipling in dog-whistle to ‘Alt Right’

The excruciating reluctance of Theresa May to condemn Donald Trump’s ban on immigrants from seven mainly-Muslim countries can hardly be a surprise.

After all, she signalled only a few weeks ago that she intends to campaign for Britain to leave the European Convention on Human Rights.

And then there was her speech in Philadelphia the night before she met the President in the White House, which triggered alarm bells for me.

Speaking to Republican leaders, she used two words that she must have known would send the right message to Trump’s closest supporters: destiny and burden.

She began predictably by paying homage to Philadelphia as the city where more than two centuries earlier the founding fathers had written “the textbook of freedom” giving written expression to the idea that “all are created equal and born free”. They had, she said, “lit up the world”.

At this point, we were within the bounds of a political leader flattering their host, even if it involves – as it did – skating over the obvious anomaly that twenty-five of the fifty-five founding fathers were slave-owners who made certain the Constitution protected their right to treat people as property.

What followed, however, was a highly significant choice of words:

“Since that day, it has been America’s destiny to bear the leadership of the free world and to carry that heavy responsibility on its shoulders. But my country, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, has been proud to share that burden and to walk alongside you at every stage.”

I could be persuaded that May and her speechwriters are philistines, ignorant of the message this passage would send, but I think it is more likely the allusions to Manifest Destiny and the poem ‘White Man’s Burden’ were deliberate.

Rudyard Kipling published his notorious verse in February 1899 in a New York newspaper as a call to the United States to “take up the White Man’s burden” by colonising the Philippines and its “new-caught sullen peoples, half devil and half child.”

The US had for three years ‘helped’ the people of the Philippines fight for independence from Spain, but this was no mission to light up the world. Rather, as novelist Mark Twain, a fierce critic of imperialism, later put it:

“We knew they supposed that we also were fighting in their worthy cause and we allowed them to go on thinking so. Until Manila was ours and we could get along without them. Then we showed our hand.”

The betrayal was formalised in the Treaty of Paris in which the United States, behaving like a European colonial power, secured control not only of the Philippines but also Cuba, Guam and Puerto Rico.

The US Senate ratified the Treaty by 57 to 27, just one vote more than the two-third required, in the face of strong opposition from anti-expansionist senators who argued it violated the Constitution.

But that was far from the end of the matter: the ‘sullen’ people of the Philippines resisted US colonisation and the war that followed saw more than 200,000 people die and led to a Senate inquiry into the atrocities and concentration camps.

In 1902, one of the opponents of the Treaty, George Hoar, told the Senate the war had been “a foul blot the flag which we all love and honor.”

For the majority of senators, however, the colonisation of the Philippines was merely a natural extension of America’s ‘Manifest Destiny’, a concept inspired by a president Trump especially admires.

May and her speechwriters will surely have been well aware that only two days before her visit Trump had hung a portrait of Andrew Jackson in the Oval Office.

The US president from 1829 to 1837, Jackson was a populist whose Indian Removal Act of 1830 paved the way for the ethnic cleansing of the Cherokee Nation from its lands east of the Mississippi.

Jackson’s expansionism was the inspiration for Manifest Destiny, a term that was actually coined in 1845 by John O’Sullivan, a newspaper editor who said the US had a right to “overspread and possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us”.

In the wars that followed, the US seized Oregon from Britain (1846) and Texas, New Mexico, California and Arizona from Mexico (1848).

The reality of Manifest Destiny was expansion through conquest, but O’Sullivan popularised it with lofty words about “the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government.”

And, today, those words are echoed by the Tea Party, which sees itself as “a choir of voices declaring America must stand on the values which made us great”.

Every political movement has its historical narrative and linguistic code. I believe May knew exactly what she was doing in Philadelphia. She wanted to send a signal to Trump’s core supporters and the words ‘destiny’ and burden’ were her code for saying: ‘I get it, I’m really one of you’.

What she hadn’t bargained for was that the President would issue his executive order on immigration on the very day they met.

Her visit to the US was suddenly over-shadowed by world-wide outrage at the ban, and she was left looking like a shifty accomplice.

Belatedly, she said she does “not agree” with the policy, but her true colours were shown by her carefully crafted dog-whistle to the ‘Alt Right’.

Steve Howell

Steve is also author of Over The Line, a novel telling the story of an Olympic poster girl tainted by the steroid-fuelled death of a friend.

Over The Line is available on Kindle (£1.99), Kindle Unlimited (free to subscribers) and in paperback (£7.99) via Amazon or post free via the secure PayPal facility on this website – ORDER