Is Nike taking athletics over the line?

Next month I will be making a pilgrimage to Oregon, the state on the US west coast dubbed the ‘mecca of track and field’ by Moroccan mile and 1500m world record holder Hicham El Guerrouj.

Oregon was where Steve Prefontaine inspired the 1970s running boom, before being killed in a car crash aged only 24 and becoming to athletics what James Dean has been to Hollywood.

Oregon’s second city, Eugene, boasts one of the most famous venues in sport – Hayward Field – which stages the US Olympic Trials and the annual Prefontaine Classic.

And its largest city, Portland, is where elite running coach Bill Bowerman joined forces in 1971 with one of his protégés, Phil Knight, to found Nike.

So Oregon has been on the bucket list for a while and everything is now arranged, including the race entry for my wife, Kim, in the Ridgeline trail run on Memorial Day weekend.

But as I watch that event, nursing my dodgy knees, part of me will feel a nagging concern that Nike – now a $28billion business – has too much influence in athletics and is using it badly.

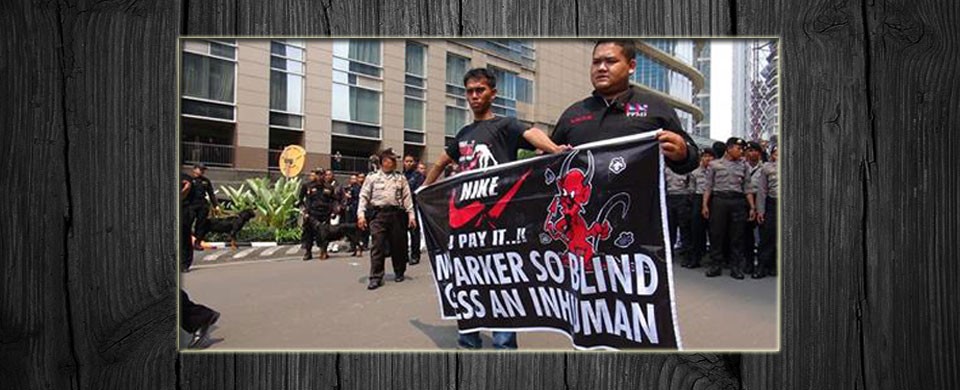

Perhaps that should be no surprise as Nike has long been accused of using sweatshops in the Far East to produce its running shoes and clothing. The company’s ‘Just Do It’ slogan translates for unions and campaign groups as Just Pay It.

In the running world, though, Nike has largely been seen as a positive force for healthy exercise and innovative kit. But in recent weeks two surprising decisions have prompted concerns in the sport.

The first came in March when it emerged that Nike had decided to sponsor two-time drug cheating sprinter Justin Gatlin.

Athletes such as Paula Radcliffe, Jessica Ennis-Hill and Darren Campbell were aghast that a man who had been banned twice would be deemed worthy of Nike cash when other top athletes have no funding.

Above all, no one could quite believe that Nike would endorse Gatlin yet, at the same time, drop Jo Pavey, the 41-year-old mother of two who won the European 10,000m title last year and is universally seen as an inspirational role model.

Soon after we had digested that unpalatable pill, along came another: the decision by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) to award the 2021 world championships to Nike’s home state without – wait for it – a bidding process.

Potential rivals were fuming. Gothenburg in Sweden, a respected athletics venue, had been preparing a bid for the 2021 event linked to the city’s 400th anniversary.

The president of European Athletics, Norway’s Svein Arne Hansen, said: “I am very surprised by the complete lack of process in the decision the IAAF has taken. (They) knew that Gothenburg was a serious candidate for the 2021 World Championships. Swedish Athletics and the city had put in a lot of effort over the years to prepare the bidding application but they have not even been given the chance to bid for the event.”

The IAAF said it had dispensed with a competitive process – for only the second time in its history – to give athletics a chance to ‘access the most powerful economy in the world’.

But its admission this was an ‘enormous opportunity’ that ‘may not arise again’ smacked of being held to ransom by the financial clout of a case presented by Nike-sponsored athletes Allyson Felix, Ashton Eaton and El Guerrouj.

After the Gatlin news broke, Athletics Weekly editor Jason Henderson wrote in a blog that he had recently bought his daughter some Nike trainers but might not have done so had he known what was coming.

“Take me back a few weeks, and I might have reversed that decision,” he said. “Now, athletes and fans alike are threatening to boycott their shoes and clothing. Yet Nike can still redeem itself by bowing to public opinion, apologising for a duff decision and telling Gatlin to take his steroid-stained CV elsewhere.”

That would certainly be a start, but it would still leave big questions about the power Nike wields in athletics and its treatment of those who make its products.

If you feel the same, you might like to join me in signing up on Facebook for Team Sweat – the support group for Nike’s factory workers. It’s time for those who love athletics to stand up for fair play both in sport and beyond.

My pilgrimage to Oregon certainly won’t include paying homage to Nike.

Steve Howell is author of Over The Line, a novel telling the story of an athletics coach whose star athlete becomes embroiled in a drugs controversy. Follow him on Twitter @fromstevehowell

Over The Line is available on Kindle via Amazon and in paperback via this website – ORDER